Reducing redundancy in convnet kernels

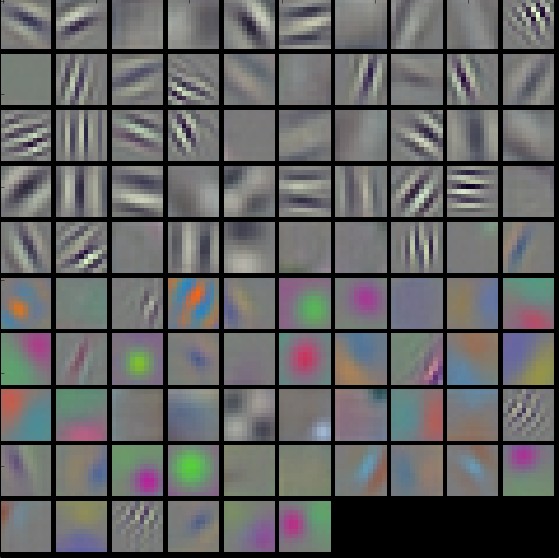

Let’s think about the kernels that are learned in modern conv nets. There’s a visualisation in CS231n:

Eg there is a neuron which has learned a kernel of approximately vertical lines, and one which has a green blob that looks like a Gaussian, and in later layers there’s probably one that detects cheetah markings – and so on.

(To avoid confusion, here we are seeing a representation of the kernels themselves, as opposed to the input images which maximally activate them.)

Now, each of these is represented by a single kernel. For simplicity let’s pretend we have kernels of size 5x5 and 1 colour channel only. That’s not a lot of information (per neuron, that is). But I want to ask: could we use a lot less?

Redundancy

Suppose we have this kernel, which would detect horizontal lines:

0 0 0 0 0

1 1 1 1 1

3 3 3 3 3

1 1 1 1 1

0 0 0 0 0

Look how much redundancy there is! All columns are identical, and there is up-down mirror symmetry also.

Is this very “clean” kernel realistic? As they say in CS231n, “Noisy patterns can be an indicator of a network that hasn’t been trained for long enough, or possibly a very low regularization strength that may have led to overfitting.” But in practice, the kernels we see are at least a little noisy and asymmetric. Eg we might have a kernel looking something like this:

0.0 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0

1.0 1.0 1.1 0.5 0.9

3.0 3.3 3.1 2.9 3.2

1.1 1.0 1.1 0.9 1.0

0.1 0.3 0.1 0.1 0.1

Or as in the image above, we might have a fairly clean-looking kernel which detects lines that are almost horizontal but not quite.

But if we see either of these cases, can’t we guess that the NN was “trying” to detect horizontal lines, and just failed because of an imperfect dataset and an imperfect training process? And so couldn’t we propose a simplification of the kernel which would change it to the “Platonic ideal” horizontal-line detector above?

Motivation

The motivation for this would be:

- each kernel uses less information (in the information theory sense);

- each kernel is potentially more robust/less overfitted, as explained by the quote from CS231n above;

- the network could become more explainable, because each neuron would be doing one job and one job only, instead of detecting something quirky like “horizontal lines, but also red blobs in the corner, sometimes”;

- that could even lead to networks being more decomposable/modular.

Too much effort?

If the processes of simplification and explanation required some manual effort for every trained network, that might not be worthwhile. But suppose there is just one vision model which is adequate as the first pass for all human-level vision tasks. This is plausible because we’ve seen that any of the big, famous modern vision models trained on ImageNet can do very well with a little fine-tuning or replacement of top layers, keeping lower layers fixed. In other words, my claim is that once we all settle on one of these big models and just use that as THE vision model (with downstream fine-tuning/network surgery/whatever), then whatever effort goes into simplifying/explaining/decomposing that model would only have to be done once. If we could understand/decompose the ONE TRUE VISION MODEL into nice Platonic kernels instead of quirky co-adapted hack kernels, it would be worth a lot and would possibly give insight into human vision too (unless that is also full of quirky co-adapted hack kernels ¯\_(ツ)_/¯).

Co-adapted kernels

Which brings up an obvious problem. If we have a highly accurate convnet and we start fiddling with the kernels to simplify them, even if it “improves” the performance of each individual kernel in terms of the job that we think that kernel is supposed to be doing, the fact is that kernels are not independent but are highly co-adapted. We’ll damage performance, if not destroy it altogether. Whatever method we use to simplify our kernels had better take account of that.

Implementation possibilities

I can think of three possibilities to accomplish the goal:

-

Before training, we could design the architecture to remove some degrees of freedom, e.g. having some 1D kernels or imposing radial symmetry.

-

During training, we could impose a new type of regularisation – a penalty on the amount of information in each kernel. That could be expressed as the number of unique values – this would push near-identical values to become identical, but unfortunately it’s not differentiable – or maybe some formulation of the entropy of the values in the kernel.

-

After training, for each kernel we could scan it and look for near-symmetries such as near-identical columns, mirroring, radial symmetry. We could then “manually” (using automated hand-written heuristics, say) change to achieve the perfect symmetry in each case. Or we could run a blur or denoising algorithm – ironically using an ancient CV technique. Once we did that for a particular kernel, we’d then freeze it and run some fine-tuning so other kernels could adapt to the changes.